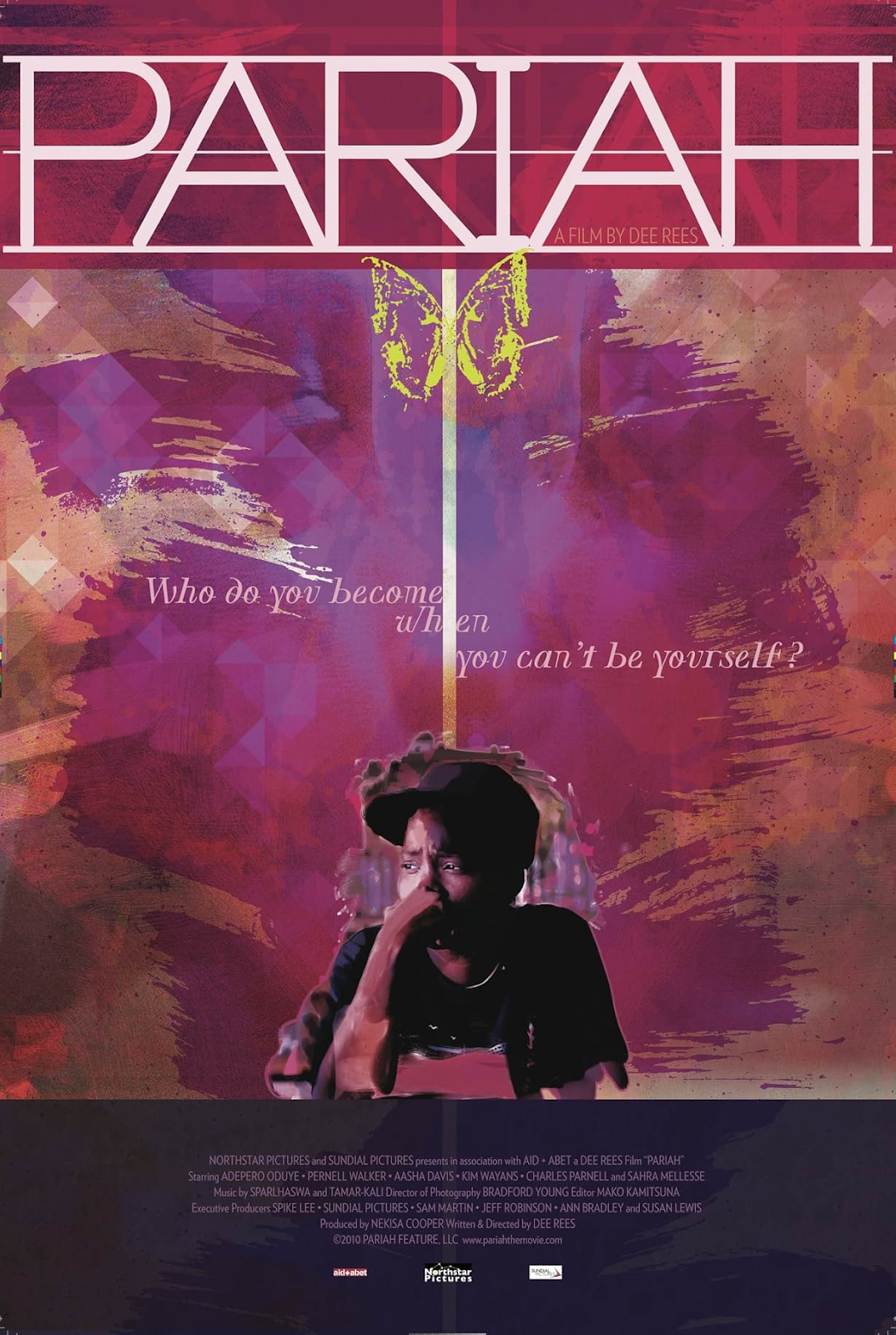

Pariah: Sexuality and Adolescence

Alike (Adepero Oduye) is a 17-year-old kid from Brooklyn,

New York who quietly embraces her lesbianism in Dee Rees’ 2011 film Pariah. It’s

a personal and vulnerable dive into the life of a black teenager who fluctuates

between performances of gender and sexuality in order to keep her secret from

her family, while also exploring what sexuality means for her as she seeks out

her first lover. Her plans are complicated by developing feelings for Bina

(Aasha Davis), and her mother’s increasing frustration with her daughter’s

“tomboy” nature. Through heartbreak and abandonment, Alike chooses herself

instead of running from who she really is.

Arguably the most prominent visual aspect of this film is

that of gender performance and how it coincides with sexuality – particularly

in black communities in New York. The film begins with Alike and Laura (Pernell

Walker) in a club, adorned in masculine clothing. Laura, who’s much more

comfortable in her skin, dances with other women, while Alike sits back until

eventually making Laura and her leave. On the way home, Alike sheds her

masculine suit and dons one that is more feminine – visually represented by a

pair of small, gold, hooped earrings. We see the opposite of this

transformation when Alike goes to school and changes from her more feminine,

mother-approved wardrobe to articles of masculine clothing in a bathroom stall.

While it’s made obvious that Alike is incredibly uncomfortable sporting

anything ultra-feminine (the scene of her mother forcing her to wear a pink

blouse to church). However, Alike’s body language suggests that even when she

emulates Laura’s transgressive way of dressing, she is uncomfortable in her

skin.

In both cases, she’s putting on these different gender

performances for the sake of other people. “This work finds that black lesbians

in New York use gender display to structure social interactions, and the order

of these social interactions maintains social control in the community. In

order to attract a person with a certain gendered style, one must possess a

complementary gender display,” writes Mignon Moore, in her study examining the

gender presentations of black lesbian communities in New York (129). While

Moore goes on to explain that these lesbians feel these norms grant a certain

agency in how they choose to present their gender, I feel like Alike doesn’t

quite feel the same level of liberation considered her transgressive attire.

Being able to dress in a masculine manner, however, does offer a way in which

to express her sexuality without having to be fully out of the closet. While

there is a freeing element to stepping out of the closet in certain circles, I

think Alike’s naivety has her mirroring how Laura presents herself, without

questioning what gender presentation feels most authentic and liberating to

her. At the end of the film, after coming out and losing her mother, Alike

chooses herself. Visually we see this in her body language – as in she’s happy

and excited about her future – but also through the way she dresses, with a

more ambiguous presentation in which she appears more comfortable.

Another interesting visual representation of queerness is

the depiction of the different stages of being in and out of the closet. The

characters of Laura, Alike, and Bina represent being out, closeted, and in

denial. Laura represents someone who has come and is comfortable in her own

skin. Laura knows who she is, and though she lost her relationship with her

mother after coming out, she isn’t ashamed of herself. Even though Laura and

Alike are close in age, Laura has a mentor-like space in Alike’s life, in which

Alike seeks her out for advice and help regarding her own lesbianism. On the

opposite side of Laura is Bina. She harbors an interest in Alike. She sees the

queerness that Alike exudes at school, and she’s curious. However, after she

and Alike hook up, she completely shuts down and claims “I’m not gay gay.”

This could give the impression that Bina tried it and just simply didn’t like

it, but a scene in the scene in which she dodges the affections of a boy

signifies something else. Bina represents someone who has discovered their

queerness but hasn’t gotten to the stage in which she’s comfortable with the

idea that she is queer. In between Laura and Bina, is Alike. She has accepted

her identity as a lesbian, but for most of the film, she’s in the closet. She’s

in this liminal space where, at least in my experience, many queer people exist

wherein she’s closeted but has found a way to be open about her sexuality in

other circles. Eventually, we see Alike come out fully, and while it’s painful

and traumatic, she ends the film in a different stage in which she is both

accepting and free with her sexuality.

Yet another portrayal in Pariah that is

representative of many queer people’s experiences is that of family. Alike has

different relationships with each member of her family. She has a very typical

bond with her younger sister, Sharonda (Sahra Mellesse), in which they argue

and throw barbs at each other. While Alike is never shown to have come out to

her sister, it’s clear that Sharonda knows just from observing her sister and

catching her in telling situations (like, for example, when she catches Alike

wearing a strap-on). Despite her little sister's urge to tattle on Alike and to

make her life generally more difficult, Sharonda is very loyal to Alike, which

is not only shown through Sharonda never divulging Alike’s secret but also in

the scene in which Sharonda seeks out the comfort in her big sister when things

get heated at home. Despite their difference, it’s Alike’s side that Sharonda

takes when Alike is forced to leave home. As for her, father, Arthur (Charles

Parnell), have a very close bond, wherein much love flows between them. Arthur

is initially against the idea of his daughter being a lesbian, but by the end

of the film, he challenges his views embraces his daughter, and makes sure she

knows that he still loves and supports her.

Alike’s mother, Audrey (Kim Wayans), is where things get

complicated. Throughout the entire story, Alike and her mother butt heads, as

Audrey desperately tries to get her daughter to be someone she’s not. While

Alike’s goal is to explore herself, Audrey’s goal is to stint the growth of

that exploration. It isn’t made clear until the coming out scene (in which

Audrey throws slurs at her daughter and hits her) that she suspects Alike is a

lesbian. Despite Audrey’s cruelty, Alike tries to bend the bridge with her

mother, but Audrey doesn’t reciprocate these efforts. Instead, she says, “I’ll

be praying for you” in response to Alike’s “I love you.” The relationship

between the two is tragic, and showcases a truth many queer – especially those

in unaccepting households – come to learn: that sometimes love isn’t

unconditional. Your family and the world will teach the message that family is

unconditional. But when you’re queer, you have to come to terms with the

possibility that your family's love is entirely conditional, and who you are is

one of those conditions, and it hurts.

Overall, this film does many things well, and it feels very

grounded in reality. I’d wager that the semi-autobiographical nature of the

film is the reason for that. It realistically weaves pain and hope in a way

that doesn’t follow the pattern of tragedy-filled queer films that came before

it. Not only does it represent queerness in a positive and grounded light, but

it also represents blackness and queerness and those two intersect. Not much

room is made for more queer people in the mainstream, even today, there’s even

less spotlight reserved for black queer people. “My assumption was that people

of color just weren’t making enough films. But that was dead wrong. Through the

better part of the last decade I’ve been working on the selection committees of

larger, industry-based film festivals in the United States,” says Roya Rastegar

at a roundtable discussion of Pariah in A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies.

“I very quickly learned that, actually, people of color, black women, queer

women of color are making lots of films. The problem is that these films aren’t

recognized as valuable, or their value isn’t legible to critics, curators, and

distributors” (430). Pariah is an example of just how valuable these

films are, and how valuable black and queer creators are. Voices like Dee Rees

deserve to be heard, and not overshadowed by a slew of white voices who don’t

make room for anyone else at the table. So many queer films feature white

people in the leading role, and I think it’s vital that black and queer artists

have equal opportunity to represent their community and tell their stories to

the world.

Works Cited

Pariah. Directed by Dee

Rees, Focus Features, 2011.

Keeling, Kara,

et al. “Pariah and Black Independent Cinema Today:

A Roundtable Discussion.” A Journal of Lesbians and Gay Studies,

vol. 21, no 2-3, edited by Mel Y Chen and Dana Luciano, Duke University Press,

2015, pp. 423-439.

Moore, Mignon R.

“Lipstick or Timberlands? Meanings of Gender Presentation

in Black Lesbian Communities.” Signs, vol. 32, no. 1, University of Chicago

Press, 2006, pp. 113-139.

Comments

Post a Comment